- Home

- Amy Timberlake

That Girl Lucy Moon Page 6

That Girl Lucy Moon Read online

Page 6

Sam Shipman came up with the idea for the postcards. Lucy Moon thought it was genius.

After taking the photos of Wiggins Hill, Sam had walked into Turtle Rock, turned left on Main Street, and continued on until he arrived at the Rossignol Bakery. He passed Mrs. Rossignol at the counter and headed toward Lucy and Zoë, who were bundled together in a blanket on the red couch. Then he reached into his backpack, got out bis camera, and turned it on.

"Look," he said, pointing to the display. He held the camera out to Lucy.

Lucy saw the camera, but ignored it. She stood up, dropping the blanket, and crossed her arms. The Rossignol Bakery was her territory. If he had come here to yell at her, she'd never let him forget it.

"Will you look at this?" Sam shook the camera in front of her face. "It's important."

"I thought you weren't talking to me, remember?" said Lucy.

Zoë stood up and grabbed the camera from Sam's hand.

Sam put his hands on his hips. "Remember making me a promise?"

That was when Zoë, who stared down at the tiny screen on the back of the camera, gasped. "Oh, no," she said. "Is that Wiggins Hill?"

In an instant, Lucy was at her shoulder. Sam took up on the other side, and all three of them stood in complete silence gazing at the image on the camera. Then Zoë slumped on the couch, Lucy crashed next to her, and Sam plopped down on the overstuffed chair opposite them.

Sam broke the silence: "Well, you're going to do something, right? Because this is bad, you know." His eyes found Lucy's.

Lucy looked away. She stared out the window at the falling snow and tried to think, but ideas were not coming. Each falling snowflake felt like a pebble dropping into her pocket, sinking her into a deeper state of despair. A fence on Wiggins Hill?

Finally, Sam picked up Zoë's hot chocolate, slugged the last of it, and banged the mug down on the coffee table. "But what are -we going to do? There isn't a law against a person who fences their own hill."

"Don't you treat my dishware like that," Mrs. Rossignol yelled from across the bakery. "I've got plenty of jobs to do for people who break things."

Two pink spots appeared on each cheek of Sam's face.

Then Sam's eyes brightened. "Hey, I got it! What if we send Miss Wiggins a postcard every time we want to go sledding?"

Lucy blinked. She looked at Zoë. Zoë stared at Sam. And then it all fell together in Lucy's mind.

"Yeah," Lucy said slowly. She clapped her hands. "Then we're only asking. Anybody can ask anything."

Suddenly, Lucy found herself thinking about being "gifted" and "talented" again—if Lucy led this protest, and if it all went well, she'd know she was "gifted"!

"Okay," Lucy said, slapping her hands down on her thighs. "We'll print up the postcard and put your photograph on the front, with a saying like ... I don't know, we'll think of that later. . . . And then on the other side will be Miss Wiggins's address and some space for sledders to ask if they can go sledding. We'll pass them out at school and tell everyone to send them. Zoë, you'll design the postcard. And Sam, you'll get your friends involved, right?" Lucy narrowed her eyes at Sam. "You're not going to bag out on me, are you?"

Sam hesitated, the pink spots reappearing on his face. Then he said, "No! Why do you think I came here?"

Zoë' seemed to be regarding Lucy. "We'll all be in this together, right?"

"Of course," said Lucy quickly, thinking that there was no need for Zoë to know that she had designated herself as leader. Wasn't that the way it usually worked out anyway?

Zoë rolled her pencil between her fingers. "Okay," she said. "I'm in." Then she added (almost defensively, Lucy noted), "And the saying should be, 'Free Wiggins Hill!'"

"Yeah, that's perfect!" said Lucy. The phrase captured Lucy's feelings about that fence.

The postcard campaign began pronto. Lucy cringed as she read the article in the Turtle Rock Times titled "Safety Calls for Fencing of Wiggins Hill."

"It's nothing personal," said Miss Wiggins. "With property comes responsibility. Unfortunately, I can't continue watching over those children sledding on my hill, and I would hate to see anything happen. It was an extremely difficult decision."

As if they were babies, thought Lucy.

So Lucy determined to make the postcard campaign a priority, despite all the other things going on in her life: first, deer hunting season didn't end until Thanksgiving, and so Lucy and Zoë faithfully wore their Killing Season bandannas every day. (Though after the first week, no one even came close to mentioning the bandannas.) Second, Lucy and her dad were still packing up her mom's studio, working on weekends and sometimes on weeknights. Her dad said that Mr. Gustafson and his construction crew would throw out anything left inside after Thanksgiving, and Lucy didn't want Mr. Gustafson's grimy, greedy hands on anything belonging to her mom. And of course there was always homework. In Lucy's estimation, junior-high teachers loved assigning homework a little too much.

But now Lucy also carried the "Free Wiggins Hill!" postcards, trying to find ways of putting them in students' hands. Sam and Zoë did the same, as well as Edna, and Lisa Alt. (Quote said she'd send a few postcards, but refused point-blank to take part in handing them out after the "debacle" of the bandanna.) The story of Lisa Alt hanging from that maple tree on Wiggins Hill had given her something of a legendary status. "My whole sledding reputation is based on Wiggins Hill," Lisa said, grabbing a pile of postcards.

For Lucy, the postcard campaign turned out to be more work than she'd expected. Lucy found out quickly enough that kids would rather gripe about no sledding on Wiggins Hill than actually do something about it. Still, as disappointed as she was in her fellow students, she didn't give up. Anyone who gasped a breath of a sentence about Wiggins Hill, or snow, or sledding, found a postcard stuffed into their hands and was told, "Just write something like: 'Wish I could sled on your hill,' and sign your name at the bottom. Don't threaten! All we're doing is asking—it is her hill, after all." If two or more kids were gathered in the hallway, Lucy homed in. Spying someone staring out the window, she would say, "I feel exactly the same way, since Miss Wiggins fenced that hill—please send a postcard!" And a "Would be nice to spend a Saturday sledding on Wiggins Hill, wouldn't it?" was said to any kid talking about weekend plans. More than one kid jumped after finding Lucy Moon at their elbows.

Over the long haul, Lucy was by far the most dedicated. Sam came in second, Lisa Alt third, then Edna and Zoë. Lucy couldn't believe how quickly Zoë had petered out. She'd lasted two weeks—that was it. Instead, Zoë spent her time altering clothes from The Wild Thrift and talking fashion. She'd even knitted a pair of shoelaces! Then one day Zoë told Lucy to give it a rest. Okay, so it was after school and Zoë was waiting for Lucy, but still.

"Everybody in this school knows about the postcards," said Zoë. "If they want a postcard they'll find you."

This made Lucy angry. "Do you want to go sledding or not?"

Zoë rolled her eyes and retorted: "Do you want to be late to the bakery or not?"

Lucy glanced at her watch. Zoë had a point. "Okay, I'm going." Then she added: "Man, I can't seem to stop."

"I noticed," said Zoë pointedly. She started walking toward her locker.

Lucy mumbled at Zoë's backside: "Better than knitting shoelaces. What do shoelaces cost—five cents?"

Zoë rounded on Lucy. "What did you say?"

"Forget it," said Lucy. "Let's go to the bakery." When Zoë continued to stare at her without making a move, Lucy added: "Do you want to be late?”

They walked down to the bakery in silence that day.

But overall, the effort seemed to be working. The postcards even made it into the hands of The Big Six in the southeast corner of the third floor. Lucy stepped out of her science class and saw Sam giving a postcard to the Genie. Sam smiled. Then his smile widened. Lucy stopped in her tracks and took in the scene. Bile rose in Lucy's stomach. The Genie had everything—body, hair, head, face, and clothes. Her shoulder-length black hair shone and turned up at the edges, reminding Lucy of cursive handwriting found in ancient love letters.

Sam and the Genie exchanged a few words. Sam laughed.

Lucy watched while absentmindedly picking up one of her braids and finding a dozen split ends.

Then the rest of The Big Six blocked Lucy's line of sight. Kendra, Brenda, Didi, Gillian, and Chantel rushed up to Sam and the Genie, asking for postcards too, please. That "please" was so sweet it would have killed laboratory mice, thought Lucy Moon. Lucy tossed the braid over her shoulder, adjusted the Killing Season bandanna on her neck, and continued to walk down the hallway. This was a test of her principles. Even though Lucy was ninety-nine percent sure that The Big Six would use their postcards as lipstick blotters or to clean dirt from under their nails, it was good for them to have the postcards just in case they had a bout of conscience and sent them. The more people that sent those cards the better, even if it was Kendra, Brenda, Didi, Gillian, Chantel, and, yes, the Genie.

Thanksgiving arrived. Lucy's dad invited two new postal carriers over to their house for dinner.

While many Turtle Rock Thanksgiving spreads included venison or deer sausage, meat was not on the Moons' Thanksgiving menu. Lucy built her own tofu turkey! She used tofu for the body, created the head out of a carved potato with a pistachio beak and a tomato wattle, and the feathers in the back were celery and carrot sticks. Finally, Lucy covered the whole thing in soy sauce. ("Turkeys are brown, Dad," she explained, when her dad tried to stop her from pouring the entire bottle on the torn.) Okay, it did look a little sickly, thought Lucy, in retrospect, but that was no reason for the postal carriers to joke. Even so, everything would have been okay if that guy hadn't poked her turkey with his fork! The turkey trembled. Then big bricks of tofu began to slip like wet soap. Lucy had to jump up and commandeer every wine and water glass to shore up the sides of her turkey. Then she gave those postal carriers a piece of her mind, which apparently, she shouldn't have done, because her dad gave her a look.

From there on out, the dinner proceeded with little noise except for the scraping of silverware on plates. It seemed to Lucy that her dad was the only one comfortable with the silence. Lucy wanted to make their guests feel welcome, but A. she didn't know what to say to two grown-ups, and B. she had just yelled at them. Anyway, the postal carriers ate a lot of canned cranberries, and said good-bye immediately after dinner. Lucy and her dad were left with mountains of dishes. Doing dishes was not one of Lucy's passions.

Worse, she was stuck in the kitchen with her dad. Lucy found being alone with her dad more unsettling than usual. Yes, she assumed that once they were alone she'd hear it for yelling at their dinner guests, but there was more to her discomfort than that. The truth was that her relationship with her dad was out of kilter, off balance. It had happened right after that phone call with her mom—the one about the studio, where her mom had been laughing and said that she'd call Mr. Gustafson, but that "probably not much could be done about it." What? Hadn't Lucy seen her mom refinish those floors and put up walls? What about the window boxes filled with flowers? And how about those times when Lucy discovered her mom there, asleep in her yellow plaid chair with a novel splayed on her lap? She loved that place!

Like a flash flood, her mom's response washed away Lucy's anger at her dad for packing up the studio. When the phone call ended, she was left with hollowness and a sense of bewilderment. Her mom was not acting like Mom. And her dad was right, when Lucy had been so sure he was wrong. It felt like the sun was the moon and the moon was the sun.

The end result was that Lucy didn't know what to say to him. Not that she'd had a lot to say before, but at least they'd had rules of engagement (avoidance and pleasantries).

In addition, ever since that phone call, he'd been talking to Lucy more, coming up with ideas for her. It was his idea she help with Thanksgiving dinner, and when she suggested building a tofu turkey block by block, he'd grimaced, yes, but then he'd said "sure." He probably regretted that now!

Lucy stared at the pile of dishes around her, and her dad's thick forearms elbow-deep in soapy water. He rinsed off a ladle and set it in the drying rack. Lucy picked it up, rubbed it dry with the dish towel, and put it in its drawer. She wished they'd turn on the radio. But they continued on in silence until her dad said, "Anything you're thankful for, Lucy?" He handed her a wineglass to dry.

Good grief, thought Lucy. She rubbed the wineglass down like it was a wire-haired dog coming out of a bath, and clunked it on the counter with the other wineglasses.

"Careful," said her dad.

Lucy ignored him. "Dad, we're not religious, so no Thanksgiving thank-yous, okay?"

Her dad gave her a look when she clunked another wineglass on the counter.

"It's not about religion, Lucy," he said. "It's about being grateful. So tell me."

"I don't know," she mumbled, threading a dish towel through a drawer handle and then pulling it back and forth.

"Come on—what are you thankful for?" Her dad passed her another dish. Lucy pulled the dish towel out of the handle, dried the dish, and put it in the cupboard.

"You want to hear what I'm not thankful for?" she said suddenly, snapping the trash can with the dish towel. "That's easy."

"Lucy . . ." said her dad.

"Okay, okay, okay." Lucy balled up the damp dish towel in her hands, sighed loudly, and began: "On this Thanksgiving Day, I, Lucy Moon, am thankful that . . ." There was a long pause as she tried to think thankful thoughts. It was like waiting for a herd of tortoises to climb a hill. Eventually, the thoughts came: "... the deer don't have to be shot at anymore. I'm thankful for Zoë. I'm thankful for free leftover eclairs from the bakery. I like my teacher Ms. Kortum. I'm glad we finished packing the studio. . . . And I'm thankful that Miss Wiggins hasn't figured out a way to keep people from snowshoeing, cross-country skiing, or starting snowball fights."

Her dad chuckled. "Yup," he said. "That sounds about right."

"Okay, well, what are you thankful for, then?" Lucy said. If he made her do it, he sure wasn't getting out of it.

Her dad smiled at her, meeting her eyes. "That's easy," he said. "I'm thankful for you."

Lucy felt something stop inside her. She turned away from him, wiping dry a dish. Why would he say that? She complained about his frozen dinners; she got mad at him for packing up the studio; and today she yelled at his dinner guests, and it was Thanksgiving of all days. They couldn't eat that canned cranberry and scoot out the door fast enough!

"Dad," she said, "I'm sorry about the studio." Lucy kept rubbing the same dish, polishing it, really. "I thought you weren't trying hard enough to keep it. I didn't know that Mom—"

"I know," he said, interrupting her. He half smiled at her.

Lucy asked the question that was in her mind. "Did you know Mom wasn't that excited about the studio anymore? Before, I mean?"

"Not really," he said. He picked up some silverware and put it in the soapy water to soak.

Lucy stared at him. "But you knew something?" She had never pressed her dad this much, but she wanted to know.

There was a pause while Lucy watched her dad gently set the gravy boat in the soapy water and then slowly work a sponge around a ring of soy sauce.

"I had a hunch," he said finally. "She never came right out and said it." He rinsed the gravy boat and handed it to Lucy.

"Oh," said Lucy.

A stretch of silence passed. It lasted through the washing and drying of water and wineglasses, forks, knives, spoons, and plates. Lucy contemplated her mom and the studio over the last summer, searching for clues. But she came up empty. If anything, her mom seemed to hang around the studio more this summer. It didn't make sense. Lucy's dad broke the silence. "What did you think of your turkey?" He pointed at the tofu rubble spilling off the platter onto the counter.

Lucy smirked a little and shook her head. "Ha!" she said.

Her dad frowned at her. "You didn't eat it? Who did?"

"You," said Lucy. She grinned. "How was it?"

Her dad took a deep breath. "Challenging," he said.

Then he handed her the tray with the remains of the tofu turkey and motioned for her to dump it in the garbage, and they both began to laugh.

CHAPTER EIGHT

December 5th—the grand opening of the "Snowy Wilderness" exhibition at Gustafson's Wild Nature Gallery and, like idiots, Lucy Moon and her dad sped right to it in the family station wagon. The windows of houses passed in front of Lucy's eyes (living rooms, kitchens, front hallways), spilling yellow light onto the snowdrifts outside. Of course, Lucy did not want to go. But because her mom had a photo in the show, her dad had insisted, saying, "We should support your mother."

This was plain dumb all around. First, on her mom's side: her mom submits a photograph to the place that kicks her out? What was that? Second, on her dad's side: how did her dad come to the conclusion that viewing a photograph meant they "supported" Mom? Her mom wouldn't be attending the show, because she wasn't physically in Turtle Rock, Minnesota—no, they'd be "supporting" a photograph. Third, her dad made Lucy put on a dress. So Mr. Gustafson takes away her mom's studio, and Lucy has to wear a dress to celebrate it!

Lucy doubted that her mom would appreciate the sacrifice she was making. In general, Lucy didn't know what to make of her mom these days. Whenever she called, she sounded so la-de-da and cheery. She didn't have much time to talk.

And then, in one phone conversation, her mom says she's not sure she wants to take portrait photographs anymore. Portraits "make her tired." What did that mean? All work makes a person tired. Lucy didn't like spelling tests, but she still studied her word lists. "Nebulous: vague, hazy, indefinite." Spelled: n-e-b-u-1-o-u-s. See? What was so bad about that? And spelling lists had to be worse than taking photos of people, talking to them and making them smile. People told jokes. Spelling lists lacked any sense of humor! Plus, what other job was her mom going to do in Turtle Rock? Waitress? A person had to keep a schedule to be a waitress, and her mom said she liked being her own boss.

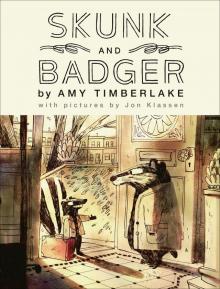

Skunk and Badger

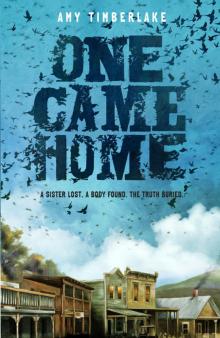

Skunk and Badger One Came Home

One Came Home