- Home

- Amy Timberlake

That Girl Lucy Moon Page 5

That Girl Lucy Moon Read online

Page 5

Lucy stiffened feeling his hand on her shoulder. Lucy hated that he didn't talk. He just decided and did. Lucy's mom would have talked to her. It was like Lucy didn't even count. She had a brain, you know!

He looked at her. "I don't want another word," he said. "I mean it."

Then he walked out of the room.

Lucy plopped down on the couch. From the living room, she heard him pull out the phone directory in the kitchen, and start calling. Within minutes, Lucy knew he was looking for packing supplies. Lucy banged her feet against the front of the couch and tried to think. What could she do?There must be something she could do!

But all she ended up thinking about was Miss Ilene Viola Wiggins. It was the second time in a month she had thought about her. First, Lucy thought about Miss Wiggins because of the arrested sledders, and now, Miss Wiggins was indirectly responsible for kicking Lucy's mom out of the studio.

Surely it was a coincidence and nothing more. No one could tell the police what to do! They took an oath, right? And as for her mom's studio, well, the lady was being generous. It had bad consequences, but so what? No, Lucy was mad at two people: Mr. Gustafson and her dad. Mr. Gustafson was taking her mom's studio away. . . . And her dad? Well, her dad was the one who was doing nothing—nada, no, not one single thing—about it.

Lucy grabbed her walkie-talkie off her belt.

"Zoë? Are you there?"

The walkie-talkie jingled when she let up her finger on the button.

Zoë answered, and within minutes, Lucy yelled her plans up the stairs to her dad, grabbed her books, and went over to Zoë's house.

Hauling, stacking, shoving, wrapping, taping, marking, and kicking—that was Lucy's weekend. Yes, they got a lot of Josephine Able Moon's Photographic Studio packed up, but it was irritating all the same. (This was where kicking came into the process—it soothed Lucy to line a box up with the other packed boxes by kicking it.)

Zoë came by with lunches from the Rossignol Bakery, and this cheered Lucy up some. But after lunch, Lucy's anger returned. Lucy knew that as soon as her mom found out about the studio, she'd talk to Mr. Gustafson and stop the eviction, and then every single one of these boxes would have to be unpacked. But until her mom called, Lucy had to pack boxes because her dad said she had to. (Luckily, her dad didn't catch her kicking them.)

The weekend came and went without a phone call from Lucy's mom, and not one message on the answering machine, either.

On Sunday night, Lucy stayed up, read her mom's last letter, and waited for the phone in the hallway to ring. The letter was sent two weeks ago from Yellowstone National Park, written on a piece of notebook paper: All the gods seem to be for me, Lucy! Her mom's handwriting looped like a roller coaster and it scrawled across the page in thick, green marker. As soon as I got to the end of the walkway, Old Faithful blew to high heaven, as fit had been waiting for me to arrive. And I feel I have arrived. This is a rich, rich place, Lucy, and I wish you could see it! This is going to be a good trip. I've sent you some photographs. Be good to your dad. Hugs, Mom.

Lucy flipped through the five photographs tucked into the letter. She had never been to Yellowstone, and couldn't get her mind around all the spurting, boiling places, so she rubbed her fingers over the glossy surface and began to think.

Hands down, Lucy's mom had the best job in Turtle Rock. Lucy wouldn't mind having her mom's life when she grew up. Lucy's mom traveled all over; she got paid to do what she loved; she owned her own business; and she lived in northern Minnesota (lakes, trees, wild animals, lots of snow). Her mom's photographs turned up in magazines, books, and art galleries. Around Turtle Rock, everyone liked Lucy's mom. When adults didn't know what to say to Lucy, they'd talk about what a "hoot" they had getting their family photograph taken at her mom's downtown studio. Close-ups of bobcats, bears, and wolves never failed to impress kids, especially when it looked like the photographer had come close to being mauled. Lucy, though, was glad that the subject of this trip—clouds— lacked teeth.

And that was the problem with the entire scenario. Lucy's mom was her mom—not some woman in a book, or a byline under a photograph, but a living, breathing mom. It was at the end of these long trips that Lucy invariably wondered if it would be so bad to have a mom who stayed home baking ginger snaps and crocheting hot pads, living solely for unending conversations with Lucy.

Nah, Lucy decided—too boring. She did not want a boring mom.

Still, she wished her mom would come home! Right now, the little red house was the land of self-enforced silent treatment, since Lucy avoided her dad as much as possible. As soon as her mom banged through the front door, Lucy planned to pull her over to the couch and tell her everything. She hadn't told her mom about The Turtle Rock Times Shuts Its Eyes yet, or asked her how a person knew if they were good at something. Lucy wanted to wait until her mom came home. Then they could talk about it forever, poring over it piece by piece.

It was only a matter of days now. It was November.

With this thought, Lucy turned off the light and slipped down under the covers. She lay on her back with her right foot off the bed. She figured this way, if the phone rang, she'd be ready to sprint. And in this position, Lucy fell asleep.

The phone did not ring that night.

Lucy's mom finally called Monday during dinner. Lucy raced up the stairs to answer the phone.

"Hello?"

"Hello, Lucy-love, it's me!"

"Mom, where are you?" Lucy had been storing up things to say for so long now, the words splattered without any regard to sentence structure. Lucy told her about the studio and how Dad started packing up the place and Lucy thought he shouldn't. She ended with, "And when are you coming home?"

It wasn't until she stopped talking that Lucy heard all the voices in the background on the other line. She heard laughter and the clinks of silverware, plates, and glassware. Someone close to the phone said, "Come on, Josephine!" And her mom laughed a sparkly laugh and whispered, "I'm talking to my daughter."

"Are you listening to me?" said Lucy. "Where are you? Are people eating? What's that sound?"

"Oh, Lucy," said her mom in the same sparkly voice, "I'm in this restaurant called Aubergine with a few friends I haven't seen in ages. And we are having so much fun catching up!"

Lucy heard someone whisper something on the other end of the line, and her mom responded, laughing loudly. It reminded Lucy of the ancient question of the tree falling in the forest and whether or not the tree made a sound if no one heard it fall. Who was her mom when Lucy wasn't there to witness her?

Lucy decided that she never wanted to think that thought again. Her mom was her mom was her mom. Lucy knew her mom.

"Mom," said Lucy, irritated. "Are you going to do something about the studio?"

"What, honey?"

"The studio, mom?"

"Oh, yeah," said her mom, sighing. "There's probably not much that can be done about it. I'll give Mr. Gustafson a call. Thank you for helping your dad pack it up." She paused for a moment and then added: "Maybe you should get your dad now. I need to talk to him, and it looks like we'll be seated at a table soon."

Lucy, feeling her time on the phone was nearly over, rushed out with her next sentence. "When will you be home?"

"Well, I'm in Banff now," her mom said, and then there was a pause that sounded like she was thinking things through. "I'm probably not going to be home this month. I've got so much to do. I'm making great contacts and seeing all my old M.F.A. buddies. The opportunities have been astounding!"

"So, Thanksgiving?"

"Probably not," said her mom. "Very unlikely."

"So when will you be home?"

"Soon, Lucy,"her mom said, sounding amused. "Now go get your dad. I need to talk to him."

"Okay," said Lucy. She didn't know what else to say. So her mom wasn't coming home in November, not even for Thanksgiving? Her mom had said November.

"I love you," said her mom.

"I love you, too, Mom," Lucy said. The words crumbled on her tongue, but she said them anyway.

CHAPTER SIX

On Thursday, November 13th, the construction workers at the base of Wiggins Hill listened to WBRR from a portable radio at the side of the road. Julie was finishing the local news.

"The Turtle Rock PTA reports they've reached only a quarter of their fund-raising goal for the new junior-high gymnasium," said Julie. "They'd like me to remind you that 'healthy children are happy children with outstanding SATs.'"

"SATs?" said Ken. "What kind of baloney is that? Shouldn't healthy and happy be enough?"

"Ken," said Julie sharply. "Please, folks," she said, in a voice thick as honey, "write a check today to the PTA. The kids need a bigger place to play."

Ken sighed audibly. "Let's have that oldie but goodie, shall we?"

"Snow Drifts, Ski Lifts, and a Hot Chocolate," an old melody from the '40s crooned through the radio as the workers erected the ten-foot chain-link fence around Wiggins Hill. The ground was near freezing now, but Miss Wiggins had paid extra for the job, and they had the equipment. It took a week. Every day they came back and dug more holes, poured cement, put in the metal poles, and attached the chain link. Each segment of fence held a sign: PRIVATE PROPERTY: NO TRESPASSING.

The construction chief lived a few towns over, so she'd never seen this hill. Man, what a beautiful piece of land— four or five maples surrounding an enormous maple in the center of the hill. Who knew they grew that big? Something about the wildness of the place made the construction chief think of her grandparents, and great-grandparents, and wonder how they'd found northern Minnesota when they settled here all those years ago.

The wind blew harder, and the air nipped colder as the construction chief attached the last sign to the fence. That's when the first snowflake fell, and then another and another and another.

She saw a boy taking pictures then, but she didn't think much of it.

The boy was Sam Shipman. He took a picture of the construction woman attaching the last PRIVATE PROPERTY: NO TRESPASSING sign on the Wiggins Hill fence, as snow fell from the sky. He snapped another, and for good luck, two more after that.

He stepped behind a tree then, to check the digital photos he'd taken, and finally found one that looked right: there was the NO TRESPASSING sign, the construction worker in front of the fence, and Wiggins Hill. He couldn't wait to see what Lucy Moon would do with this!

A fence on Wiggins Hill? Sam was so mad he could spit. Losing deer-hunting privileges was nothing to losing sledding on Wiggins Hill. (Sam liked deer hunting, but it also had its mind-numbing parts, like sitting in tree stands for hour after hour after hour.) He knew what his parents would say about the fence: "That's disappointing, Sam. We're sorry." And his teachers wouldn't care, just "Get that homework done." But Lucy Moon would get indignant, and then she'd go after Miss Wiggins.

Sam was going to pit two evils against each other, like the ancient rivalry of the mongoose and the cobra. That was Sam's plan.

Lucy Moon and her fake promises! Every parent he knew was talking about The Turtle Rock Times Shuts Its Eyes. "No one will know it's you," Lucy had said, solemn as a priest. Sam had looked into those brown eyes and believed her. What a dummy! He could kick himself for it. Sam had decided never to talk to Lucy again.

Until this happened. Fencing Wiggins Hill was plain cruel. Snow and no sledding? Look, but don't touch? Miss Wiggins was the cobra. Lucy was the mongoose.

Out of the two, the mongoose was Sam's favorite animal. If he were truthful, he'd have to admit that, before she cost him deer hunting, Sam had kind of admired Lucy. She was fierce. He liked how her eyes burned when she talked about things that were important to her. But Sam supposed the thing that really made him think about Lucy was that interview. She had listened. She didn't tell stupid jokes or make wisecrack comments while he and Lisa told their story.

Not that he wanted her as a girlfriend.

But if she took care of this fence, he'd be so happy, he'd forget about missing deer hunting.

She was still going to have to admit that her promise had been bogus.

Anyway, first things first—they had to deal with the fence.

Lucy Moon and Zoë Rossignol sat on the big red couch in the Rossignol Bakery. Lucy had spread her math book out on the coffee table in front of her, and Zoë sat nearby knitting an orange-and-olive cable sweater. Every so often Zoë asked Lucy what answers she got. "Good," said Zoë. "I got something like that, too."

That was when Lucy felt a small tug inside her. She looked up. And through the big plate glass window, she saw snowflakes blowing sideways, puffed out like the sails of boats. Snow! In her mind's eye, Lucy took a nosedive down Wiggins Hill—the rush of air, her cheeks numb with cold, her braids blown backward, and plummeting, plummeting, plummeting down the hill.

Lucy whispered very, very quietly (she might scare it away): "It's snowing."

Zoë lifted her eyes to the window and stared, the knitting needles frozen in the middle of a purl stitch. "Is that really snow?" she said. Zoë finished the stitch and stuffed the knitting into her bag.

More and more snowflakes began to fall, lines of them, filling the windowpane with white.

Lucy grabbed Zoë's hands, pulled her off the couch, and the two of them ran for the front door.

Mrs. Rossignol yelled: "Lucy and Zoë, you wear your coats!" But it was too late for that. The bakery door dinged, and Mrs. Rossignol watched them run full speed up the sidewalk.

Lucy and Zoë ran with all their might up and down the sidewalk, yelling and wailing. They were a sight: Lucy wearing her favorite wool shirt and hiking boots, and Zoë slipping around in a pair of ballet shoes, teal tights, and fuzzy blue skirt. (Grover fur, Zoë called it.) Finally, they stopped to catch their breath, stuck their tongues out to taste the snowflakes, and started shivering. So they ran back inside the bakery and begged Mrs. Rossignol— please, please, please—for another hot chocolate.

Drinking their hot chocolate (and wrapped together in a blanket Mrs. Rossignol found in the back office), they sat on the couch and stared out the window.

Lucy said, "It looks like it'll be enough."

Zoë absentmindedly kicked one of her wet ballet slippers. "If it snows all night."

"Will your mom let you, after the arrested sledders?"

Zoë grinned. "Oh, she doesn't care about that."

Lucy smiled. At that moment, nothing—not one thing—felt insurmountable. Not even the fact that her mom would not be home for another month. Who cared? Now she could finally go sledding on Wiggins Hill.

That's when the door to the Rossignol Bakery dinged, and in walked Sam Shipman.

CHAPTER SEVEN

After that first November snowstorm, the clouds continued to bring snow to Turtle Rock—no blizzards, but steady, steady, workaday snow. There was light, dry snow—barely visible, but making the air and everything seen through it sparkle. There was the kind of snow that came assembly-line fashion, one snowflake rushing after the next. This snow lasted all day and into the night. And then there were the big flakes that floated out of the sky, drifting like daisy petals—"She loves me . . . She loves me not . . . She loves me." The snow piled up in curls, outlining trees, causing the tops of pines to bow under the weight. When the wind blew, long strands of snow combed over land and road.

The largest sugar maple on Wiggins Hill held out its snow-festooned limbs, and the five smaller sugar maples reflected the larger tree's glory, while the surface of the hill smoothed downward in polished rolls. The perfection of the hill's snowy surface was a sledder's dream. No footprints, no sled tracks, only wind shivered across its surface.

At first, many adults found themselves feeling rather huffy about that fence. Who did Miss Wiggins think she was talking to when she posted private property: no TRESPASSING every five feet, like they didn't get it? They were not "trespassers," thank you very much. Oh, they knew that technically Miss Ilene Viola Wiggins owned that hill. It's just that Wiggins Hill felt like communal property, as close as a piece of land could come to being a public park without actually being one.

Then they sighed and recollected that time (a decade ago, at least) when that young Doug what's-his-name from Duluth had tried to get the city council to ask about buying Wiggins Hill. They called him "citified," and said that he was "raised suspicious."

"No," the city council had said. Turtle Rock was a community: a place where people worked together for the common good. There was no need to own Wiggins Hill, and they had better places to spend their severely limited funds.

But no one wanted to hurt anyone's feelings by reminding them of that missed opportunity—no, there wasn't a thing to be gained by dredging up the past.

Then Turtle Rock residents reminded themselves of all Miss Wiggins did for Turtle Rock: the hospital, the reference wing of the public library, the pipe organ at the Lutheran Church, the movie theater (with all those wholesome G-rated movies), and the Baroque music concerts. Every other week she appeared in the newspaper for helping out with something. Wasn't that worth trading a little sledding for?

But even after all was said and rationalized, a primal injustice stirred in the hearts of many in Turtle Rock, seeing that hill and that sugar maple noosed with a chain-link fence.

The kids stared at the fence, the hill through the fence, the snow falling from the sky, and found life and its promises unfair. Here they'd waited weeks, while weather forecasters promised snow that never came, and then when it finally snowed, the hill was fenced—NO TRESPASSING. Now they'd never be able to try out their new saucer sleds on the best hill in town, or find out if Lisa Alt had been telling tales about getting snagged by that sugar maple. Suddenly, kids found wool sweaters itchier than normal, board games wimpy, and television blundering and stupid.

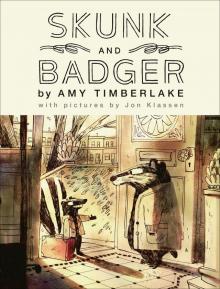

Skunk and Badger

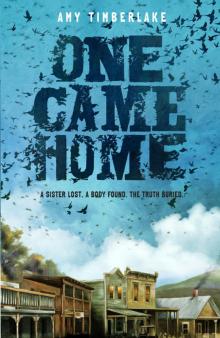

Skunk and Badger One Came Home

One Came Home